The world pays tribute to Mandela (slideshow)

As South Africans come to terms with the loss of former president Nelson Mandela, the rest of the world bids farewell to Madiba.

Pimples: Saving Madiba's rabbit (video)

Gwede, Mac and Blade try their best to stop the rabbit from whispering in Mandela's ear. But the elusive animal has some tricks up its sleeve.

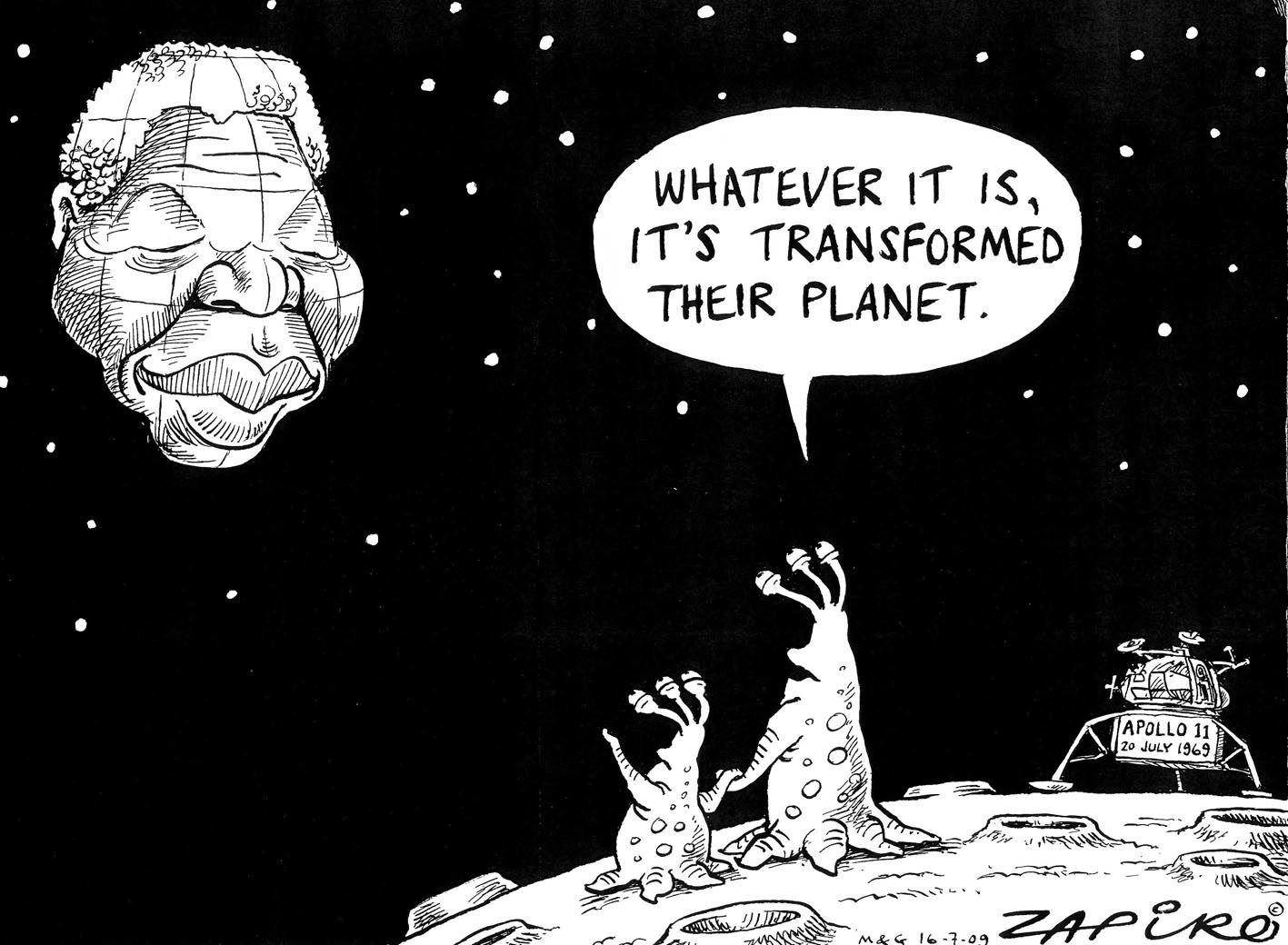

Zapiro's best Madiba cartoons (slideshow)

From his toughest moments to his most triumphant, Madiba has been an inspiration. Here are some of our favourite Zapiro cartoons about him from 1994 to 2013.

Mandela: SA's greatest son laid to rest (slideshow)

The world watched as Nelson Mandela was finally laid to rest in his hometown of Qunu following a dignified and moving funeral ceremony on Sunday.

Makaziwe Mandela remembers crying when her father was sentenced to life imprisonment 23 years ago. She was nine, and she cried because older children at her boarding school told her he was going to die.

A teacher comforted her. He explained that the children had got it wrong: Nelson Mandela's ringing declaration in a South African court that he would fight to the death did not mean he was going to die -- but that he would right for freedom all his life. Mandela is now 69. He is, of course, still in a prison cell and his fight for freedom goes on.

Makaziwe -- she's known as Maki -- is 32 and his eldest daughter. She is a child of Mandela's first marriage: his ex-wife, Evelyn, once a nurse, now runs a trading store in the Transkei village of Cofimvaba.

Mandela has four surviving children. Two are from his first marriage: Maki and her brother, Makgatho, 34, who works in the Transkei trading store. Mandela's second marriage, to Winnie, has produced two daughters: Zeni, married to a Swazi prince, and Zinzi, who is studying at the University of Cape Town.

Maki has been in the US for the past year on a Fulbright scholarship at the University of Massachusetts, working on a master's thesis on rural women in South Africa. Next year she wants to go on to a PhD, and is interesting in moving to Britain to specialise in Third World studies at York University.

She is married to a Ghanaian educationist, Isaac Amuaha, and has three children: a daughter, Tukwini, 12, and two sons, Dumani, 10, and Kweku, who is nearly two.

Makaziwe has not had much time to get to know her father. Her parents were divorced when she was very young, but she saw him over weekends: he and Winnie were living close by in Soweto.

After he was jailed, she had to wait until she was 16 before she was allowed to visit him. She recalls once writing to him in jail about a personal problem. "Maki," he wrote back, "don't make me regret I'm here. I do not want to come to the point where I regret what I'm doing. What I need to do is worthwhile, not only for you, but for all black people."

But he has desperately missed his children, she says. The worst time for him was in 1969, when her older brother, then 24, died in a road accident. "This was hard for my father, more than anything," she says. "The government did not let him attend the funeral."

A love of education has been a legacy from her father. She remembers that, right from her early years, he insisted that she receive the best possible schooling. That was difficult to accomplish in South Africa so, at her father's insistence, she went to school in Swaziland and stayed there until finances and border problems made it too difficult; she had to complete her schooling in Soweto.

"He encouraged me to continue my studies," she says. "He told me I could not help the people unless I was educated." She went on to complete bachelor's and honours degrees in South Africa. But to her father's disappointment she swung away from the scientific career he wanted for her and developed an interest in women's problems.

She wants to return to South Africa eventually, to put her knowledge to work in rural communities, to help women upgrade their status. She has always avoided political involvement. She is usually a reserved person, keeping her laughter for those she knows, and applying her quick, bright mind to her academic studies.

When she went to America last yew, she intended to stay in the background, not seeking any special role as her father's daughter. But during the past few months she has emerged in public as a passionate and articulate champion for her father, attacking the system which keeps him imprisoned, and propounding his political outlook.

She has accepted speaking engagements and television and radio interviews. Her shyness disappears when she stands on a public platform: there is raw emotion as she tells of the misery of life under apartheid. She says her father will accept freedom from his life sentence only if his release is unconditional.

"He's our leader until he dies," she says. "He is not a violent man, but he will fight on. He believes in peaceful change, but his attempts to negotiate have been turned down. "He will never give up."