The world pays tribute to Mandela (slideshow)

As South Africans come to terms with the loss of former president Nelson Mandela, the rest of the world bids farewell to Madiba.

Pimples: Saving Madiba's rabbit (video)

Gwede, Mac and Blade try their best to stop the rabbit from whispering in Mandela's ear. But the elusive animal has some tricks up its sleeve.

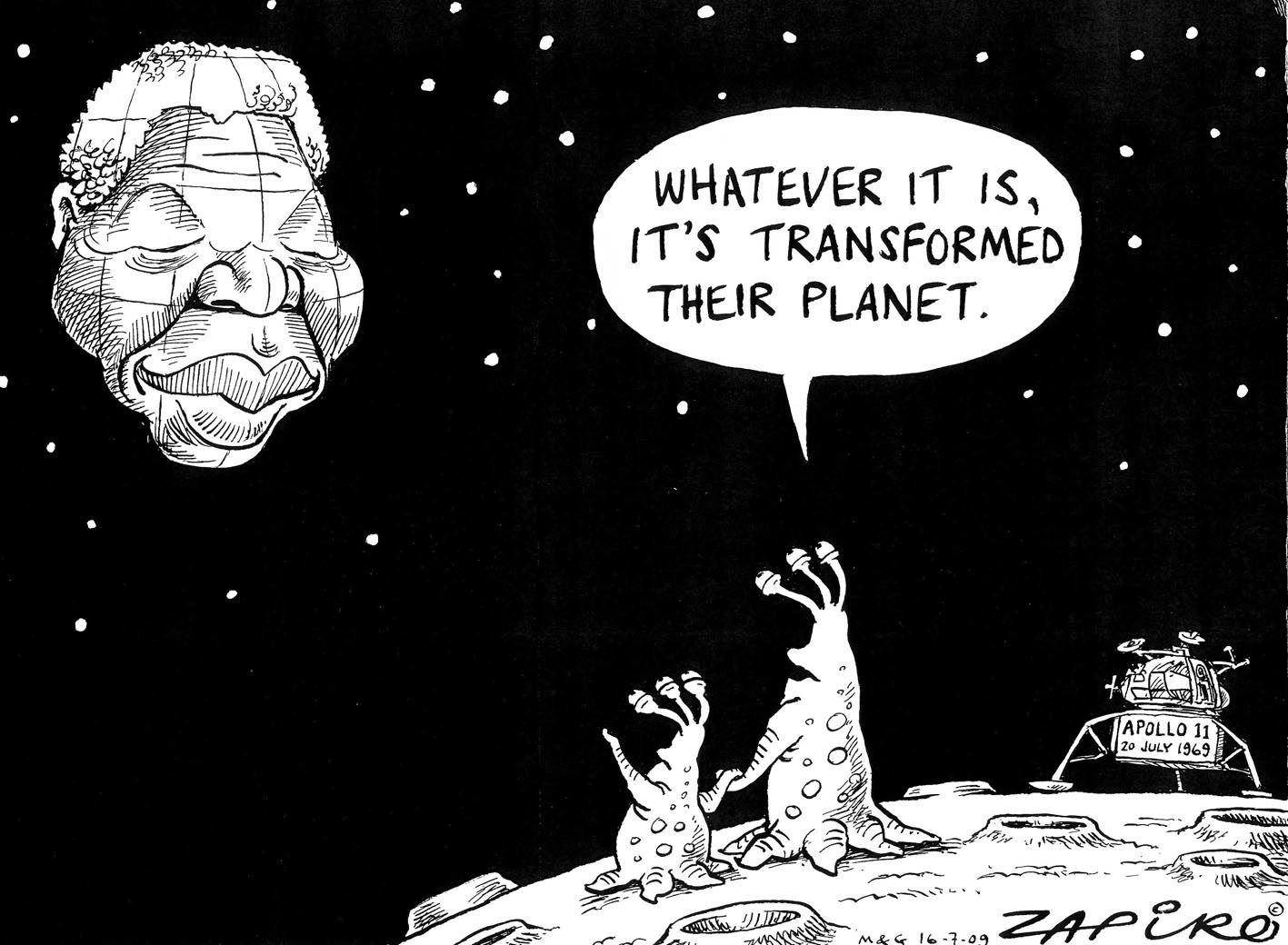

Zapiro's best Madiba cartoons (slideshow)

From his toughest moments to his most triumphant, Madiba has been an inspiration. Here are some of our favourite Zapiro cartoons about him from 1994 to 2013.

Mandela: SA's greatest son laid to rest (slideshow)

The world watched as Nelson Mandela was finally laid to rest in his hometown of Qunu following a dignified and moving funeral ceremony on Sunday.

The old man did not use his friend's surname, Mandela, the name by which he is known all over the world. Nor did he call him the Leader, the name used by the many who support him. I thought he would use his Xhosa name, Rolihlahla. He called him, simply, Nelson. In his quiet way, the old man looked up and smiled. Yes, he had seen Nelson in Pollsmoor Prison. They had talked for an hour before the old man was released from prison, where he had been for 24 years. At the time, it was lid that the government was showing compassion.

The old man's health was failing; so they freed him. Others suggested that his release would be a trial-run for freeing Mandela. It would test whether the most important political prisoners could be freed without apartheid opponents bringing South Africa to a halt He did not want to comment on whether he had come - like John the Baptist - to prepare a way for Nelson's coming, and seemed con fused that I had put the question in this way. Many, many had come to welcome the old man. It is said that there had never been such a crowd at Jan Smuts Airport when the old man journeyed there. And outside the building where he talked to the press, the traffic was stopped. But the old man’s freedom was short Iived; he evoked such emotion that the government restricted him to the city where he lived before he went to prison. He is not allowed to make public statements or give speeches. But he was not alone. Many came from all over the world to see him and ask about Nelson, the others in prison and the politics of South Africa.

I asked him where it was that he had met with his friend. The old man described Nelson's cell with quick gestures - a book-shelf against the wall, pen and paper on a table and a bed. Almost as an afterthought, he added that Nelson read copiously, including newspapers and magazines from all over the world. Thoughts of the place where Nelson Mandela has spent his days had struck me. In the old man's apartment the furniture was shiny-new modern. Not a picture hung against the wall. Strange this. The average person retains an odd stick of furniture or a memento to hang on a wall to show for more than 20 years of life. But from prison one brings only memories of friends and hopes for the future.

Certainly, Mandela too will bring few material goods with him, even though he is one of the most famous men in the world, and even though his picture hangs on many, many walls. If the authorities were planning to release Nelson what would be the impact on the country, I asked. He thought for a moment, then drew an analogy with India. The South African situation was not a one-person struggle. Nelson was not a Mahatma Gandhi; there were too many factors at play. Nelson recognised this and knew that the complex political process would continue. No, the people would have to be patient and discipline; there was no other choice. But restraint would be rewarded in the end. He was worried, however, about the whites: how to convince them that the best way forward was to break with their past and make a new beginning. As I travelled home, I thought about the old man, his friend, this troubled country and what he said about it.

Botha's decision to release Mandela will certainly change the political landscape. The circumstances under which Mandela will be released will be crucial. If it will be, as some suggest, a "grandfather release" - effectively retirement with his family - this will be unacceptable to Mandela, the African National Congress, the international community and democrats within the country. There is thus no alternative to an unconditional release. In this event, what will be the reaction of the whites which the old man feared? There will be those who will accuse the government of being soft on communism and violence.

Foreign Minister Pik Botha has indirectly warned the rightwing Conservative Party that their recent actions will undercut any international gains, which might follow Mandela's release. But the South African government itself runs that risk through its half hearted measures. The release of Mandela alone, without the unbanning of the ANC and the initiation of a broad political dialogue, will not end South Africa's endemic political travail or its international isolation.

Professor Vale is the director of the Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University

This article originally appeared in the Weekly Mail.