The world pays tribute to Mandela (slideshow)

As South Africans come to terms with the loss of former president Nelson Mandela, the rest of the world bids farewell to Madiba.

Pimples: Saving Madiba's rabbit (video)

Gwede, Mac and Blade try their best to stop the rabbit from whispering in Mandela's ear. But the elusive animal has some tricks up its sleeve.

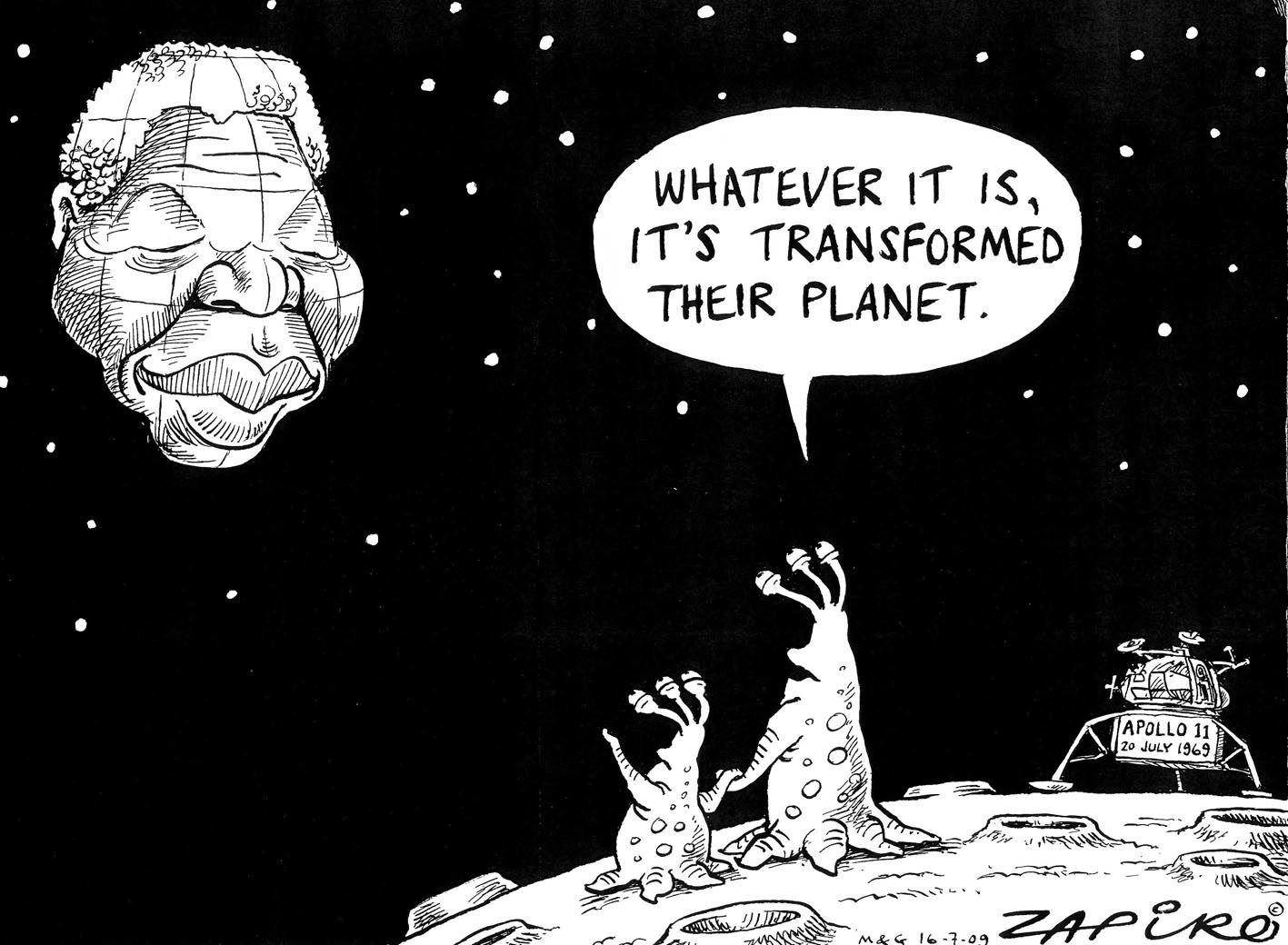

Zapiro's best Madiba cartoons (slideshow)

From his toughest moments to his most triumphant, Madiba has been an inspiration. Here are some of our favourite Zapiro cartoons about him from 1994 to 2013.

Mandela: SA's greatest son laid to rest (slideshow)

The world watched as Nelson Mandela was finally laid to rest in his hometown of Qunu following a dignified and moving funeral ceremony on Sunday.

Prison letters, rare as they were, were -- with even rarer prison visits -- Nelson Mandela's contact with the outside world. Through pen and paper he was often called upon to be the father, husband and partner to the family apartheid had conspired he would be away from at the times they needed him most: to praise them in their moments of pride and comfort them in times of grief and sorrow.

It is quite possible that no individual has popularised the isiXhosa word for father, tata, like Nelson Mandela. With the clan name Madiba, tata is the name that has become South Africa's first democratically elected president's "other" name.

Yet for a select group of little people, the name meant more than a grand nickname. It was a call each child makes to the one man from whom they expect protection, reassurance and guidance. And for a long time this group of children could not access the privileges other tatas discharge without thinking twice.

The children's tata had made some difficult life choices and that meant that he could play the role only through letters, which he could send only once a month. In one of the letters (written on February 2 1969) to his children, Mandela plays the proud dad on hearing that his children have fared well in school:

"The nice letter written by Zindzi reached me safely and I was indeed very glad to know that she is now in standard two [grade four]," he wrote to "Misses Zeni and Zindzi Mandela" of House No 8115 Orlando West, Johannesburg.

Mandela expressed joy that his children from an earlier marriage, Kgatho and Maki, also passed their exams. He took pleasure in learning of the young Zeni's culinary skills:

"I was happy to learn that Zeni can cook chips, rice, meat and many other things. I am looking forward to the day when I will enjoy all that she cooks."

Despite expressing his wish, though, Mandela could not, at the height of apartheid, create false hope that his freedom was around the corner. He writes: "Zindzi says her heart is sore because I'm not at home and wants to know when I'll come back. I do not know my darlings, when I will return. You will remember that in the letter I wrote in June 1966, I told you that the white judge had said I should stay in jail for the rest of my life. It may be long before I come back, it may be soon. Nobody knows when it will be, not even the judge who said I should be kept here. But I am certain that one day I will be back at home to live in happiness with you until the end of my days."

In another letter, written in September 1970, Mandela wrote to the minister of justice petitioning for the right to be by the side of his ailing wife, Winnie, ahead of her trial and so that they could deal with some domestic issues. The two had not seen each other since December 1968.

The letter is a sequel to two he had written to the commissioner of police after Winnie's detention in May 1969: "There are urgent domestic problems which we cannot properly solve without coming together. In examining the letter you will bear in mind that there is nothing in law and the administration of justice to preclude me as a husband from having consultation with her while she is facing trial, political or otherwise. On the contrary, it is my duty to give her all the help that she requires. The fact that I am prisoner ought not in itself deprive me of the opportunity of honouring the obligation that I owe her."

But the letter he wrote on July 16 1969, upon receiving news from the warders' commanding officer of a telegram reporting the news of the death of his son, Thembi, in a car accident three days earlier, must rank among the most difficult tasks any parent has to perform.

Writing to Evelyn, his first wife, he says: "I write to give you, Kgatho and Maki my deepest sympathy. I know more than anybody else living today just how devastated this cruel blow must have been to you for Thembi was your first-born and the second child that you have lost."

He continues later. "The blow has been equally grievous to me. In addition to the fact that I have not seen him for at least sixty months, I was neither privileged to give him a wedding ceremony nor to lay him to rest when the fatal hour had struck."

Mandela adds: "I looked forward to further correspondence [from Thembi] and to meeting him and his family when I returned. All these expectations have been shattered for he has been taken away at the early age of 24 and we will never again see him."