The world pays tribute to Mandela (slideshow)

As South Africans come to terms with the loss of former president Nelson Mandela, the rest of the world bids farewell to Madiba.

Pimples: Saving Madiba's rabbit (video)

Gwede, Mac and Blade try their best to stop the rabbit from whispering in Mandela's ear. But the elusive animal has some tricks up its sleeve.

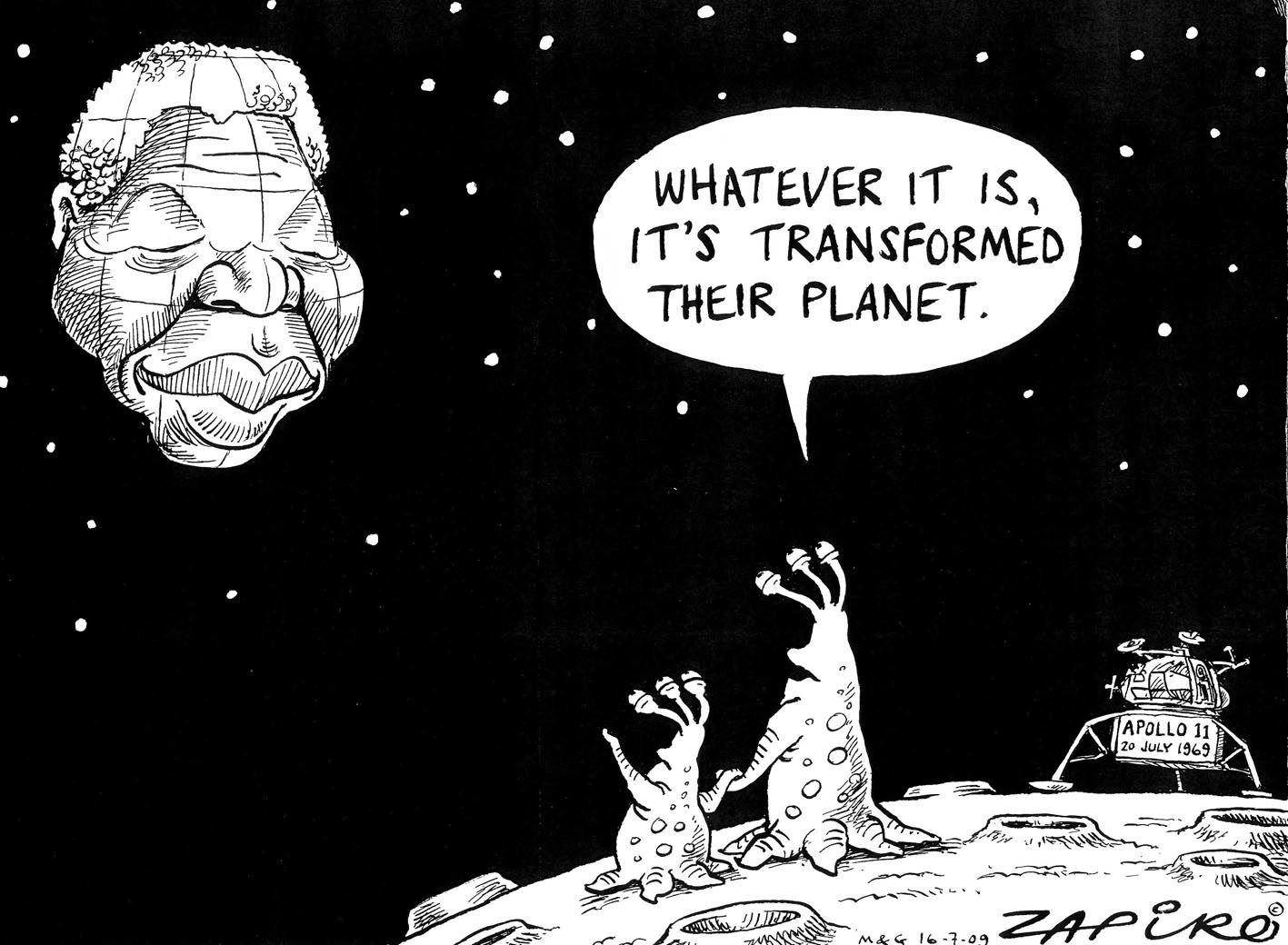

Zapiro's best Madiba cartoons (slideshow)

From his toughest moments to his most triumphant, Madiba has been an inspiration. Here are some of our favourite Zapiro cartoons about him from 1994 to 2013.

Mandela: SA's greatest son laid to rest (slideshow)

The world watched as Nelson Mandela was finally laid to rest in his hometown of Qunu following a dignified and moving funeral ceremony on Sunday.

Amina Cachalia, who died aged 82 on January 31 this year, would have loved the printed version of her autobiography because it was so much like her: bright, colourful, glamorous and gorgeous.

Although she saw a proof of When Hope and History Rhyme (Picador Africa), she never held a copy of the final book. Cachalia died suddenly from a perforated ulcer in a Johannesburg hospital, five weeks before it was in the bookstores.

Her autobiography not only tells the epic tale of the resistance against the brutality of apartheid, how the struggle for a non-racial, non-sexist democracy was achieved, but also of the triumph of ordinary people in how they battled the evil system.

But Cachalia wasn’t just an ordinary person. In When Hope and History Rhyme — named after a poem by Seamus Heaney — she describes her involvement in the Women’s March on the Union Buildings on August 9 1956 when 20 000 women marched against pass laws for black women. She also tells of her life as a leader in the progressive movement, as a person who was banned for 15 years and how her husband, Yusuf, was placed under house arrest and banned for 27 years. And she gives a very frank account of her close relationship with Nelson Mandela.

But she was also a mother to Ghaleb and Coco. Earlier this month I met with them at Coco’s Johannesburg office to talk about the autobiography and other things, especially what it was like being her children.

“It was wonderful being Amina’s daughter. Amina was the celebrity of the family, as everybody will tell you,” says Coco. “Everybody that was vaguely important that came to our house didn’t come because of Yusuf, they came because of Amina — from those years and subsequently onwards.

“She was an inspiration to everybody out there but, in her home, she did the business of being a mother and she did it damn well. So we lived these rather strange lives to many people — I was sent off to boarding school, as was Ghaleb, at the age of whatever; we were sent to London. Prior to that, we grew up in a household where there were banning orders and house arrests; it wasn’t a normal life in many ways. But, in spite of that, there was never an idea that we were being short-changed. I never felt that.

“Maybe the Slovo girls felt that from Ruth [First, their mother], as they poignantly said in pictures and films that they made before, but, with Amina and Yusuf, it was a loving home.”

Did being referred to as Amina’s daughter instead of as Coco ever upset her? “It never did. My mother in a sense played a role way beyond a role I will ever play. I’m sure she went on marches to the Union Buildings and she did all the big things but she also did the little things that were visible to us on a day-to-day basis.”

Extraordinarily trying circumstances

Ghaleb also had a wonderful relationship with his mother. “My father was a very philosophical man, a very wise and dignified man who never raised his voice, who, when you did wrong, sat you down and all you wanted was to get a klap so that you could go out and play. But he kept you for an hour telling you that in a Hegelian way this was not right …” Ghaleb laughs at the thought.

“My ma was very different, you got the klap from her, okay! She was forthright, in your face, had a temper but was extremely comforting, extremely loving; she was always there for you, in every single way that a son or a daughter would want.

“From a nurturing point of view … from looking after all the bits kind of way — your teeth! We had good teeth because our mother made sure we wore bloody braces all our lives.

“It was extraordinarily trying circumstances … here’s a father house arrested and a mother banned, the father going to jail, the mother occasionally going to jail, passports being denied, security policemen prying into their lives, people forget — even I forget — how brutal the regime was, and certainly younger people have no concept of that brutality.

“And, within that life, we had an enormously wonderful home life, no small thanks to my mother.”

The government refused to replace a teenaged Ghaleb’s lost passport — he was stuck in the United Kingdom and couldn’t come back to South Africa for several years. Didn’t he sometimes think, I just want a normal life?

“We were taught from an early age to wear the privations the government visited on us as a badge of pride.” He punctuates this with his hand on the table. “And whether we did so overtly, implicitly or covertly, it was part of our nature. I never for one minute thought, shit, can I have a normal family life? My life was normal under the circumstances. I had a great childhood — I was 15 when I lost my passport and I was sitting in England. Ja, I missed my father and mother, but I also had a jol!”

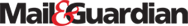

One of the best parts of the book is the selection of photographs.

“My mother had an incredible eye for a camera,” says Ghaleb. “If she walked into a room and there was a camera, she would find that camera and the camera would find her.”

Coco adds: “She was a great giggler. My father at one point decided that he needed to teach us Urdu and there were some things that sounded extremely funny … he would make us repeat them and we would burst out laughing and we would giggle and giggle.”

Meetings with Madiba

Throughout her life Cachalia was the embodiment of the non-racial ethos. “She had friends — not acquaintances — friends, who were hairdressers, friends who were simple women, friends who were deep-thinking social and political activists, like Helen Joseph, Ruth First, Hilda Bernstein, Rica Hodgson, friends who were frivolous people who she had fun with,” says Ghaleb. “My father had relationships with his political peers. My mothered straddled A to Z effortlessly, able to be at home wagging her finger at President Mandela, down to relating to the man in the street.”

Talking of Mandela, he features prominently, especially towards the end of the book. Cachalia tells of how she was linked romantically to Madiba — there was speculation in the Sunday Times that she could the next Mrs Mandela. There was also the time when she visited him at his Houghton home. On her way out, “as he was walking me to the door, he stopped, gathering me in his arms and kissed me. I was somewhat taken aback by the intimacy of the embrace.”

All of that happened before Mandela got married to Graça Machel on his 80th birthday on July 18 1998 — the marriage, by the way, came as a huge surprise to Cachalia. “The poor fellow did not have the guts to tell me the truth,” she writes in her autobiography.

Coco only became aware of Madiba’s feelings for her mother when she read the book. “I never knew that!” she says. “We always knew … that Nelson had a very great liking for my mother. Of that there was absolutely no doubt. All his interactions with her, the amount of time he spent in our household, even prior to my father’s death [May 9 1995], Nelson was a constant feature in our home.

“And Nelson was a constant feature in our home because of Amina, because he had a very strong affection and bond with her. He had a strong political connection to my father but he had a much stronger personal connection to my mother.”

She turns to Ghaleb: “In fact, I don’t know if you remember all those rumours of him getting married, the number of people who came up to me to ask if he was marrying Amina. It was an open secret in lots of ways … And he is a flirt — I don’t think she was the only one historically or subsequently.”

But Ghaleb was aware of it because “I worked very closely with my mom on the book, so I knew — it evolved and I revisited things with her, I teased things out of her and told her she can’t just elude to things cryptically and told her she had to tell the whole truth. So it wasn’t a revelation to me once it was published — I was part of the genesis, if you may.

“In the written drafts, the references initially to Mandela were very cryptic, and I’d say, ‘Ma, if you want to write this book you can’t drop a little cryptic thing here … People are going to ask questions, they’d want to know, you’ve got to either say or cut it out, it’s a choice you make. I would advise you not to cut it out because you’re telling everything in this book so you must talk about it’.”

What did she say to you, did she agree?

“She said, no, it is very difficult and I don’t know if I want to do it. So I said, think about it.

“Then I said write about it, as if it were not for publication and then we can jointly sit and see what we need to weave into the publication, which is what we did. But it was a bit sneaky of me because I couldn’t just sommer put it in there.”

Coco: “I think, if she had her way completely, she wouldn’t have put it all in.”

Ghaleb: “But she had the right to veto. I said to her afterwards, ‘Ma, if you’re unhappy with anything, take it out.’ It was all there, it was on paper, and she thought about it. I don’t know if she discussed it with you?”

Coco: “No, no …”

Were you shocked?

Coco: “I think it was couched in the context of knowing there was this subtext that was there previously … I was surprised but I can’t say that I was totally shocked.”

Ghaleb: “Do you remember she called us one day and she said that Madiba had asked her to marry him?”

Coco: “Yes, yes …”

Ghaleb: “And she doesn’t talk about it in the book. And I said to her, ‘You’re alluding to various things and I think there was a degree of …’ I don’t know why she didn’t want to say it because she called us and she said to both of us, ‘He asked me to marry him and I don’t want to marry him’. But she didn’t put that in the book — don’t ask me why.”

Cachalia finished the book four months before her death. “We are incredibly lucky that we have this book as a legacy,” says Ghaleb, “and the timing is just so astonishing.”

Both children find it extremely hard to come to terms with her sudden death, although she was 82. There was no warning, no run-up; just a rather routine hip replacement operation, and she came out well from that. But then she had a perforated ulcer and she was desperately ill for two weeks before she died.

“And that was it,” says Coco, looking vulnerable. “So we didn’t have any huge preparation around my mother’s death.

“It is all terribly raw and sometimes I scratch my head, thinking, she should be here, she shouldn’t be dead. It is a very difficult thing.”