The world pays tribute to Mandela (slideshow)

As South Africans come to terms with the loss of former president Nelson Mandela, the rest of the world bids farewell to Madiba.

Pimples: Saving Madiba's rabbit (video)

Gwede, Mac and Blade try their best to stop the rabbit from whispering in Mandela's ear. But the elusive animal has some tricks up its sleeve.

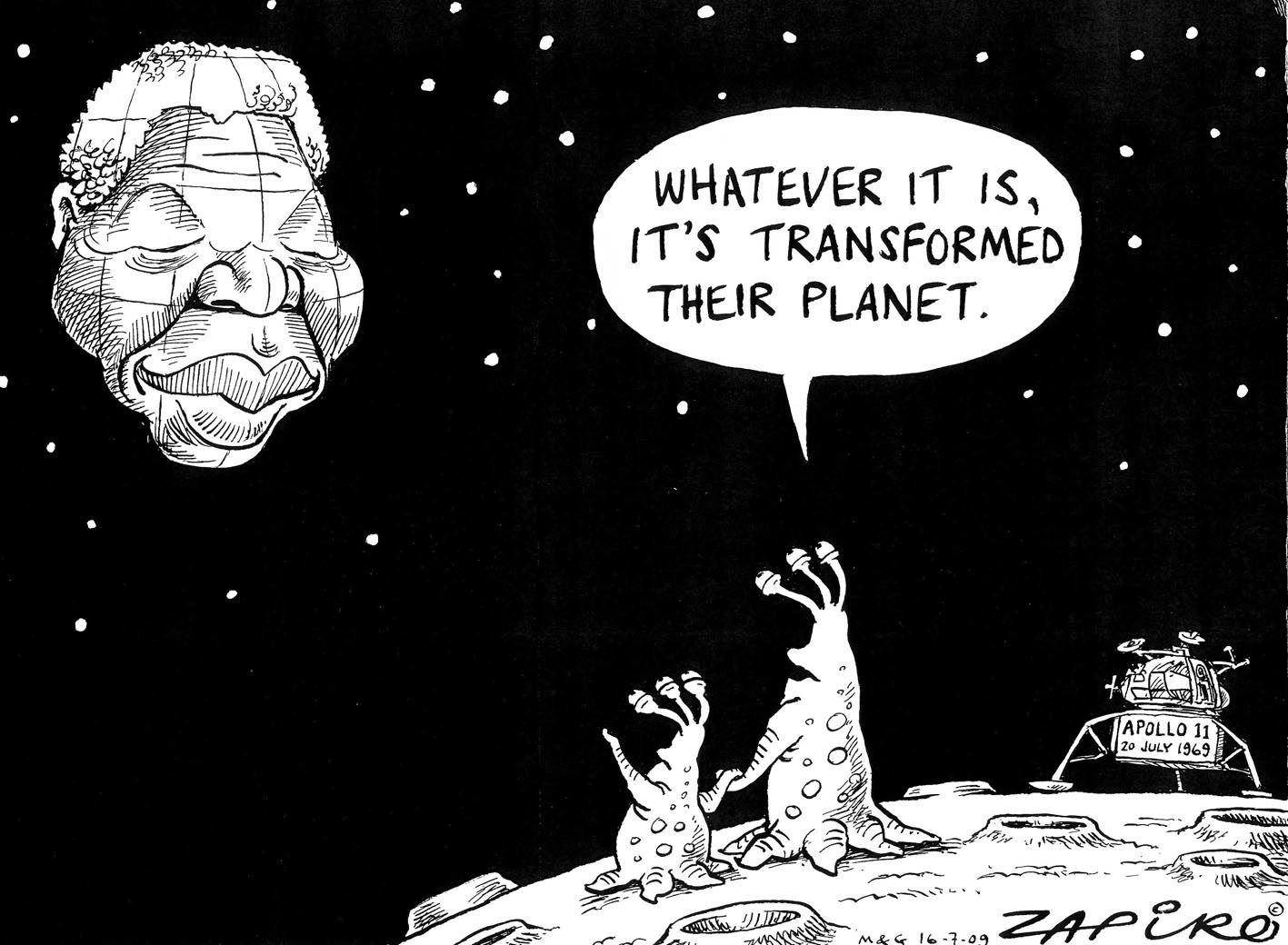

Zapiro's best Madiba cartoons (slideshow)

From his toughest moments to his most triumphant, Madiba has been an inspiration. Here are some of our favourite Zapiro cartoons about him from 1994 to 2013.

Mandela: SA's greatest son laid to rest (slideshow)

The world watched as Nelson Mandela was finally laid to rest in his hometown of Qunu following a dignified and moving funeral ceremony on Sunday.

News that our beloved former president Nelson Mandela's health has been downgraded to critical has left South Africans preparing for the inevitable. On Sunday night people started recounting their favourite memories of the icon on social media, as if to ease themselves into the process of mourning him when he leaves us – an event that draws closer every day.

We are in the third week of his hospital stay, again for a recurring lung infection. Before this, in that strange limbo period while we waited and sometimes forgot that Madiba was in hospital, international media houses tried to keep the story going. Local journalists and analysts were drawn on to provide commentary as newsrooms around the world watched the year's biggest story unfold.

I received a few queries, one from an Australian radio show. It was a quick phone interview on June 16: a Youth Day that poignantly happened to fall on Father's Day in our country this year. I tore myself away from friends and family to take the call late on Sunday night as the Australian dawn broke many kilometres east.

We chatted about the weakening rand, the upcoming 2014 elections, youth unemployment and, of course, Madiba's health.

Then the presenter dropped the question that left me momentarily speechless.

"Are there fears that there will be race riots when Mandela dies?"

The presenter was affable, interested and respectful, so I didn't hold it against him personally when he asked the question. He was clearly just reflecting what was a common question and sentiment in his home country, and perhaps the world: the idea that South Africa was a boiling pot of violent racial tension with one lone crusader planted between warring factions, brokering a tenuous peace.

I tried to explain that the work of reconciliation was not due to one man, or even one party. I spoke about our democratic transition being the work of many groups, religious leaders, parties and, of course, the South African people themselves. He moved on to our violent race-related crimes. "South Africa does have high levels of crime, yes, but it's mostly unrelated to race," I said. "Our racial tension is largely non-violent." I also added the caveat that extremist groups and individuals existed – who would of course disagree with me (as they will with this column, which the comment section will no doubt evince) – but that they were in the minority.

I rang off to rejoin my loved ones, silently fuming. Of course I should have expected this, should not have been surprised – especially given the ridiculous stories that dogged us in foreign media around the time of the World Cup. English tabloids in particular ran farcical stories of "machete wars" in the streets of South Africa ahead of the monumental international sporting event that we ended up running incredibly well, much to the disappointment of the naysayers and doomsday pundits. I even brought this fact up with the deejay: "We laugh at the stories you guys sometimes write about us around the world."

But what really saddened me was this distorted idea people had of Mandela. Did they think so little of the work that he and others like him did to believe that it still depended on them at this stage?

No. True leadership – the sort of visionary leadership that Mandela is famed for – leaves a legacy that outlasts its originator's mortal flesh. It bequeaths an idea that can live on without him or her, an idea that will take root and flower despite the intense and sometimes ugly obstacles thrown at it. And reconciliation, that painstakingly tough, monumental but necessary project, is one that belongs to all of us now. The notion that we would dissolve into race riots at the news of Mandela's death is so unlikely as to be ridiculous, and that is precisely thanks to the work of Mandela and others. They can leave us peacefully knowing their bit has long been done.

Those who suggest otherwise are far removed from the reality that Mandela has created in this country: a reality that will long outlive him. If only they understood that Madiba, at the end of his life, will do the same thing he did throughout it – bring us closer together.