The world pays tribute to Mandela (slideshow)

As South Africans come to terms with the loss of former president Nelson Mandela, the rest of the world bids farewell to Madiba.

Pimples: Saving Madiba's rabbit (video)

Gwede, Mac and Blade try their best to stop the rabbit from whispering in Mandela's ear. But the elusive animal has some tricks up its sleeve.

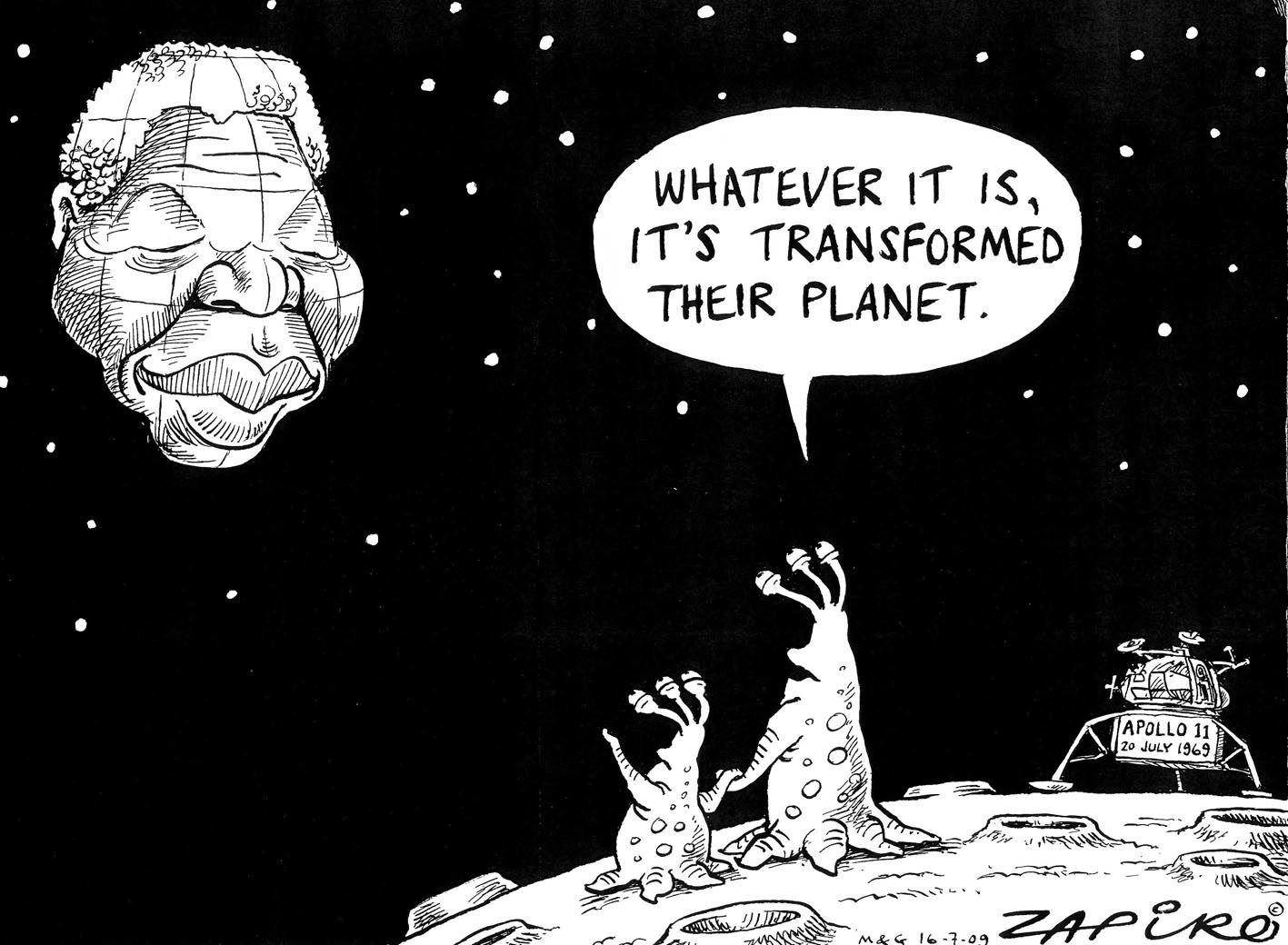

Zapiro's best Madiba cartoons (slideshow)

From his toughest moments to his most triumphant, Madiba has been an inspiration. Here are some of our favourite Zapiro cartoons about him from 1994 to 2013.

Mandela: SA's greatest son laid to rest (slideshow)

The world watched as Nelson Mandela was finally laid to rest in his hometown of Qunu following a dignified and moving funeral ceremony on Sunday.

In truth, we've said goodbye to Nelson Mandela many times before. As our president in 1999, as our omnipresent inspirational figure when he stepped out of the public spotlight in 2004, and then a handful of premature goodbyes as the world hung anxiously on news of his deteriorating health.

This goodbye should be the final one, but it doesn't feel that way. It's as if this moment, which we have grudgingly rehearsed so many times, is still just a simulacrum of a grief that our nation, and indeed a large part of the world, must necessarily experience again and again.

Nelson Mandela stands for so much in our national psyche, is so much a part of the vocabulary we use to understand and express our present and future struggles, that we can never really let him die.

We needed him then, we need him now, and we will always need him. He was, is, and always will be the lodestone to which our national voyage must tend.

In an editorial six months ago, we spoke of Mandela's goodbyes as a bestowal , a way of turning the absence of his person into the presence of his example.

We wrote of the profound withdrawal from public life that he began in 2004, a withdrawal which we saw as an insistence that South Africa learn to get along without his guidance, overt or implicit.

As much as he may have sought peace after a life of constant struggle, Madiba was also teaching a basic lesson: this must be a nation of laws, and of institutions, not of men, certainly not of one man.

At the time of Mandela's withdrawal, some of us did not want to let him go, besieging him with pleas for intervention, for anointment, for the sheer, unrivalled, force of his being at World Cup bids, fundraisers, and election events.

In the space of his refusals, a Mandela industry grew up designed to protect him and his legacy, but clearly, naturally, incapable of embodying him, and at times susceptible to glib shorthand.

Now, at this awful point of his death, is the time to reject that easy legacy, and to embrace the infinitely more complicated truth of the man.

Others were all too hasty to see him off, to welcome the lacuna left by his gracious absence.

As our transition progressed, and in some ways soured, Mandela's tough-minded commitment to reconciliation based on the restoration of justice was caricatured by critics as too soft, too forgiving, inadequate to the increasingly urgent project of a deep transformation in South Africa's power structures, and in the lives of millions of still-immiserated people.

For them Mandela could be dismissed as an ANC leader who made white people and foreigners feel comfortable, at a time when discomfort was needed.

This too we must reject as a facile re-engineering of his force, a force that defies the containment that would render it mute.

An incapacity to recall the radical demand of Mandela's humanism, and a tendency to congeal his personality in bronze and branding, however, may be the least of our failures.

The truth is that Nelson Mandela has been absent not just from banquets, front pages, and the high councils of the ANC, for close to a decade. He has too often been absent from our conception of ourselves, and the messy, joyous work of building a democracy in which the full realisation of our individual and collective humanity is possible.

The ANC, which he regarded as essential to the transformation of our national life, without which, he said, "I would be nothing", is struggling amid factionalism and greed to recall his 2009 injunction "to let the good of our people always remain supreme in all our considerations".

This is why today's goodbye must not be final.

Tomorrow, we will need Mandela again, to imbue us with the spirit, the intelligence, and the humanity to carry on the flawed, essential legacy he has gifted us.

At the opening of the first democratic Parliament in 1994, Mandela quoted Ingrid Jonker's poem The child who was shot dead by soldiers in Nyanga.

The final words of that poem seem as apposite to the death of Nelson Mandela as they were to the birth of our nation.

"the child is present at all meetings and legislations

"the child peeps through the windows of houses and into the hearts of mothers

"the child who just wanted to play in the sun at Nyanga is everywhere

"the child who became a man treks through all of Africa

"the child who became a giant travels through the whole world

"Without a pass."

We say goodbye to our giant.

But we must refuse to say goodbye to his example, his ideals, and the dream we share with him.

We will always need Madiba.