The world pays tribute to Mandela (slideshow)

As South Africans come to terms with the loss of former president Nelson Mandela, the rest of the world bids farewell to Madiba.

Pimples: Saving Madiba's rabbit (video)

Gwede, Mac and Blade try their best to stop the rabbit from whispering in Mandela's ear. But the elusive animal has some tricks up its sleeve.

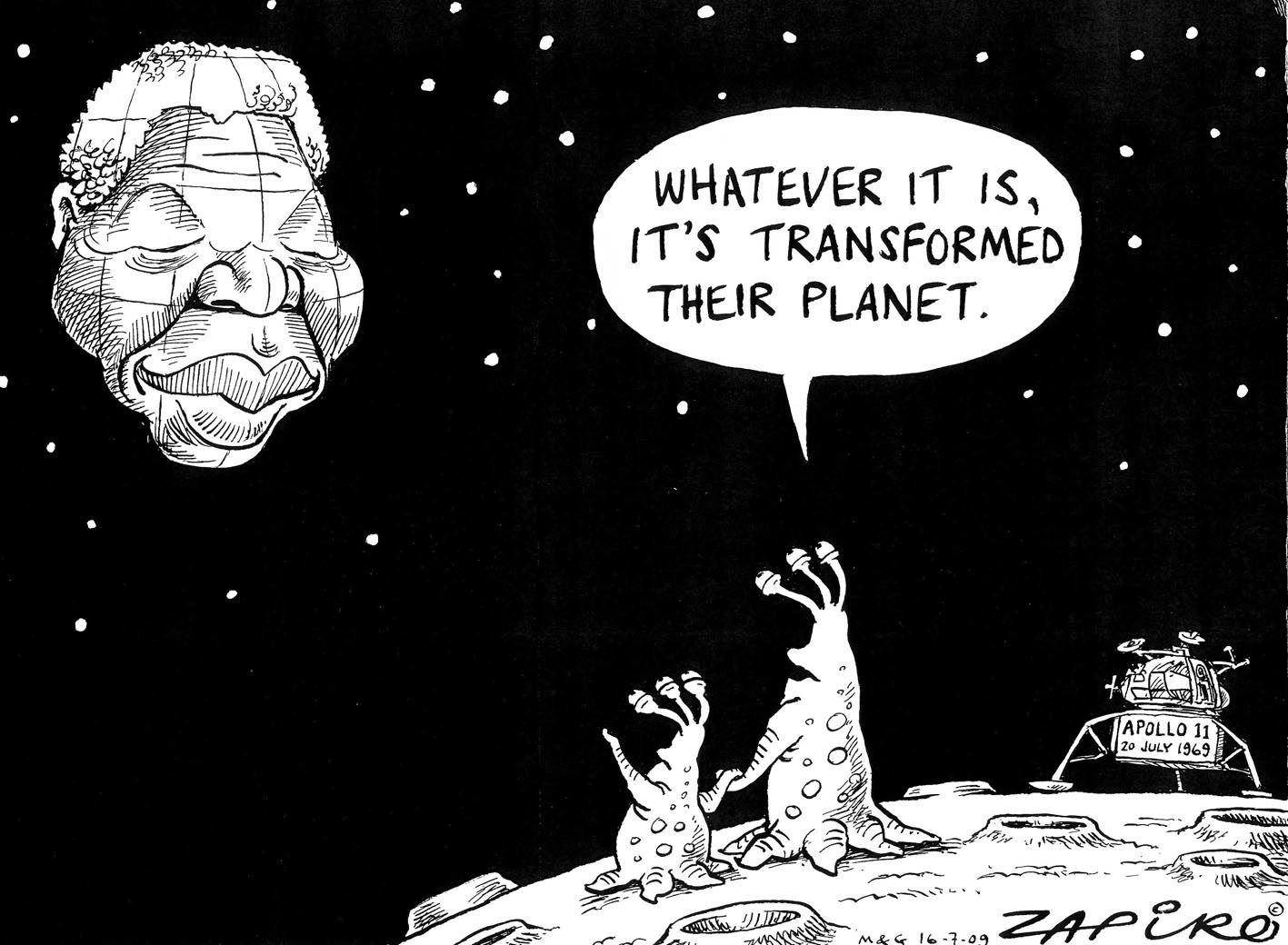

Zapiro's best Madiba cartoons (slideshow)

From his toughest moments to his most triumphant, Madiba has been an inspiration. Here are some of our favourite Zapiro cartoons about him from 1994 to 2013.

Mandela: SA's greatest son laid to rest (slideshow)

The world watched as Nelson Mandela was finally laid to rest in his hometown of Qunu following a dignified and moving funeral ceremony on Sunday.

On a balmy autumn afternoon in April 1999, at about half past three, the then 10-year-old HIV activist Nkosi Johnson was becoming increasingly restless.

"How long are they still going to be?" he asked his adoptive mother, Gail Johnson, while rubbing his hands together and staring at the pictures of state leaders on the big white walls around him.

The frail and tiny boy was seated on a large floral couch in the reception area of the presidential guesthouse in Pretoria. He had rushed from the launch of his and his mother's first Nkosi's Haven, a shelter for HIV-infected mothers and their babies in Johannesburg, for what he considered one of the most important appointments in his short life.

Nkosi was going to meet president Nelson Mandela. But the great man's helicopter had not arrived. Nkosi said he was not interested in meeting the woman who had been crowned Miss Universe and who was accompanying Mandela; what was important to him was that he was about to meet a "kind, tall man" who he knew would not discriminate against him.

When the entourage finally arrived, the president walked up to Nkosi, shook his hand and asked him: "So, young boy, what would you like to be when you're big?"

"A policeman," Nkosi answered quickly. "Nothing else."

A police uniform was familiar to Nkosi – his mother had been a police reservist.

"Oh, not a president?" a surprised Mandela asked.

Nkosi paused for a few seconds, mulled the question over, and said: "No, it looks like too much hard work" – to the president's obvious amusement.

SA presidents and HIV

Nkosi died of Aids two years later, but his words proved to be prophetic. Being a president in South Africa when it came to the issue of HIV would be extraordinarily difficult.

Although Mandela had spoken publicly about the potentially devastating impact of HIV on South Africa as early as 1992 at the launch of the National Aids Convention of South Africa, he had been criticised for hardly addressing the issue after becoming president in May 1994.

Constitutional Court judge and HIV advocate Edwin Cameron said it was not through a lack of trying.

"We begged everyone around him to get him to make a major speech on Aids but it only happened in February 1997 [at the World Economic Forum session on Aids in Davos, Switzerland], nearly three years after he took office."

At the forum, Mandela referred to Aids as "a new struggle" and said: "When the history of our time is written, it will record the collective efforts of societies responding to a threat that has put in the balance the future of whole nations. Future generations will judge us on the adequacy of our response."

History indeed recorded the effects of a lack of action during his presidency: government figures show that the HIV infection rate among pregnant women nearly tripled during Mandela's presidency, from 7.6% in 1994 to 22.4% in 1999.

Building a new country

Mark Heywood, head of the advocacy group Section27, said that, although it was to Mandela's and his government's credit that they oversaw the creation of a far-reaching Aids plan, it was not implemented during his presidency.

"Serious political leadership in those years on HIV could have helped us to prevent a significant number of new HIV infections," Heywood said.

But both Cameron and Heywood emphasise that there were other priorities at the time while "Mandela was building a new country".

"Tragically, the political agenda, in a sense, blinded people to something [HIV] that would later undermine the ideals of that agenda, such as dignity and equality," Heywood said.

On the other hand, he said, there was "Mandela's own conservatism, traditionalism and fear at that stage about speaking out about something that involves sex".

After stepping down as president, Mandela openly regretted not doing more about the pandemic, but also about the lack of time to do so. The South African Press Agency reported that he said: "It's no use crying over spilt milk … I had no time … I had to concern myself with nation-building."

Mbeki and dissidents

The astonishing thing, Cameron said, happened when Mandela left office and forced history back on a positive track through courageous steps that involved publicly opposing his successor, Thabo Mbeki, who had become sympathetic to the views of Aids dissidents.

The dissidents' views included beliefs that HIV did not cause Aids and that antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) were therefore an ineffective way of treating the virus. This resulted in Mbeki's government being resistant to making ARVs available, "engulfing the country in a horrific crisis of death and suffering", according to Cameron.

At the International Aids Conference in Durban in 2000, Mbeki's dissident views were exposed in a very public way when he implied in his opening address that poverty, and not HIV, was the cause of Aids. The young Aids activist Nkosi Johnson, who was also a speaker at the opening, did not get as much as a handshake from Mbeki.

A major legal battle was brewing between the health department and a powerful HIV activism group, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), about access to ARVs that could prevent HIV-positive pregnant women from transmitting the virus to their babies.

When Mandela closed the conference a few days later, he made his own position clear: "This is the one event where every word uttered, every gesture made, had to be measured against the effect it can and will have on the lives of millions of concrete, real human beings all over the continent and planet … [We have to ensure that people have access to] measures to reduce mother-to-child transmission."

According to Heywood, Mandela's change of mind, and what some would call his "last crusade", was partly driven by the TAC's opposition to Mbeki and its countless demonstrations, and partly by Mandela's love for children: "HIV killed parents and left behind thousands of orphans. I believe it helped to wake him to the human dimensions of the epidemic."

Mandela turns activist

On February 7 2002, Mandela took his public endorsement of the science of HIV a step further when he awarded the Nelson Mandela Prize for Health and Human Rights to two University of the Witwatersrand researchers, James McIntyre and Glenda Gray, who specialised in HIV treatment for pregnant women and who had both publicly criticised Mbeki and his health minister, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang.

"The next day, just a few hundred metres away, Parliament was to open and president Thabo Mbeki was to deliver his State of the Nation address. The juxtaposition seemed significant," Cameron writes in his book Witness to Aids, for which Mandela wrote the foreword. "What many suspected in Madiba's choice of date and venue became unmistakable as he delivered his address."

Four months later, in June, and a few days before the Constitutional Court would force the government to make HIV treatment available to infected pregnant women, Mandela visited HIV activist Zackie Achmat. Achmat was HIV positive, but refused to use ARVs until the government made them available in the public sector. Mandela wanted to persuade him to take his treatment, but was unsuccessful.

But on December 13 that year, on Friday exactly 11 years ago, the former president did something that astounded Achmat and made him change his mind. Mandela was visiting an HIV clinic of the humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières on the Cape Flats and had put on a T-shirt emblazoned with "HIV positive", which TAC supporters had been wearing in marches and which had become "a symbol of the struggle for justice and reason and openness in the Aids debate", Cameron said.

It was a few days before the national conference of the ANC.

"That moment, I realised that I could take my pills because what he had done then was to take a stand against a party that he had given his life to," Achmat says in an interview published on his website. "Mandela's support for the TAC turned the tide. It helped to save two million lives."

Talking about HIV openly

Then, in January 2005, during a time when discrimination against people with HIV and their relatives was extremely high, Mandela announced that his 54-year-old son, Makgatho, had died of Aids. The only way to combat this virus, he said, is to talk about it openly.

"To say that his son had died of Aids was to bring HIV right into his home in a way that putting on a T-shirt didn't. It said to people: 'If my son could die of HIV, then you can accept and talk about the fact that people in your family may be dying of HIV too," Heywood said.

Cameron summarises Mandela's contribution: "There were three indispensable components that led to South Africa having the biggest ARV programme in the world: civic society, the courts and Mandela."